|

'My film flopped and Hollywood didn't want to touch me'

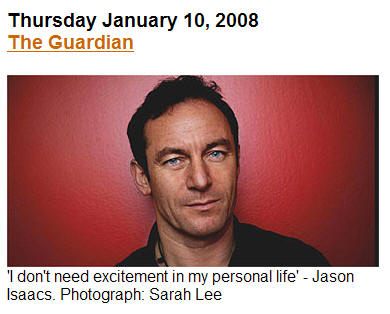

Jason Isaacs has the kind of face that is hard to remember, and I mean that as a compliment. It's not that he's average-looking - he's not (it's those glinty pale blue eyes) - but somehow he manages to disappear into each role he plays. I don't think he was too offended when I told him I had never heard of him (I know, I'm charming). What I remember instead are his characters. One of the most extraordinary, in 2006, was Chris in Scars, a low-budget one-off Channel 4 film in which Isaacs played a real-life violent offender. Or the villainous British colonel in The Patriot. Or the deliciously camp Lucius Malfoy in the Harry Potter films. Or the ethically challenged British ambassador in the BBC drama The State Within, for which he has been nominated for a Golden Globe. The event has now been cancelled because of the ongoing writers' strike, but like many of the stars, Isaacs says he wouldn't have crossed the picket line.

The strike also means that the future of his television series, Brotherhood, is uncertain. Isaacs, 44, plays Michael Caffee, a small-time gangster who returns home to his Irish-American neighbourhood in Providence, Rhode Island, after years on the run, just as his brother Tommy's career as a local politician is stepping up. The second season has just started in the UK, but in America, the writers' strike means that the third series is in limbo. Isaacs got the part in Brotherhood after he had gone to Los Angeles to "salvage my career". He had appeared in Peter Pan, the 2003 film, which flopped, even though Isaacs says he still believes it is the best film he has ever made. "I was in 'Hollywood jail' - nobody would touch me because I had been at the centre of this very expensive flop," he says. While he was there, he was offered a small part in a couple of episodes of The West Wing. "I did it and loved it. Then I was offered the pilot [for Brotherhood] and it was beautifully written and, frankly, I was feeling unloved by the film world." With his family based in London, did he think about the implications of being signed up to a long-running US TV series (he is contracted for six seasons)? "People urged me to think very carefully about it. I emailed a friend who is in a very successful American TV series" - no, he won't say who - "and he wrote back, saying, 'Don't do it. It screws your other work up, it splits your family up, people in Britain forget who you are, other projects won't take you on ...'" He acknowledges that it is a mixed blessing. Brotherhood is an intelligent series with great writers, and he gets paid very well for it, but it also means spending five or six months a year in Rhode Island, and his eldest daughter, who is five, has just started school in London. When asked about the secret behind his relationship with wife Emma Hewitt, who he met at drama school - they have been together for 20 years and have two daughters - he says they have tried not to be separated for too long. "I get to experience great extremes in my work life," he says. "I'm murdering, loving, saving, exploding, sobbing, fighting. So I love the simplicity of making my kids scrambled eggs and reading them stories. I don't need excitement in my personal life." The other secret, he says, is that they are both "insanely in love with being parents. It would be wrong to say I have no ambition left, but I have no ambition left that isn't for their benefit." Professionally at least, Hewitt, a former documentary maker, has been the one to make the sacrifices. "She decided she was going to give up a very successful career and follow me around and live, with nothing to do, in these far-flung places, and not really feel like part of the crew, in order to get pregnant," he says. "It took us a while and we had IVF, which worked first time for us both times." It is his wife, he says, who has always kept him grounded. We start talking about why there are so many "cunts" (yes, his word, but no, he doesn't name them) in the film industry and I wonder aloud why he doesn't seem to be one. "My wife would kill me," he laughs. If Isaacs has a strong desire to keep his family happy and nurtured, it doesn't take a psychologist to work out that his own childhood has a lot to do with it. He was brought up in Liverpool, the third of four boys, in a close-knit Jewish community. His mother raised their sons while his father, who had left school at 14 to become an apprentice, worked in the jewellery trade. "There was no atmosphere of the arts in my life," he says. "I'm not saying we were deprived. We went to the panto once a year, we had a stereo in the garage where we could go and listen to music. But nobody played an instrument; we had a collection of leather-looking plastic-bound classics that lived on a shelf and were never opened. It was not an option to go into the arts." He says he doesn't remember his childhood happily. "I don't mean that anyone was cruel to me; it was probably internal. Everybody did their best, but I don't think it was a particularly happy household. There were arguments. Things are different now, but I don't think my brothers and I were kind to each other. It was only really when I was in my early 20s that I began to recognise that there was value in being kind to people as opposed to putting up a very contemptuous defensive barrier so nobody could get to you. "There was a sense, growing up in a little Jewish community, that this mysterious outside world beyond those walls would be out to get you. My parents were teenagers when the war was over, and they found out the unbelievable horror that happened just a few hundred miles away that could have happened to them. So there's a sense of isolation ..." Did that instil a fear in him? "I think it probably did and it took a long time for it to melt away. My first real contact with a large number of non-Jewish people was when I went to university. They were alien and strange creatures. That has evaporated, thank God, because it's a siege mentality, but I understand where they got it from. I didn't feel when I was younger that I was a welcome citizen of anywhere actually, probably other than Israel." Didn't he feel British? "I didn't. I do now but it doesn't matter to me, being defined. I don't really feel any more English than I feel American, or I don't feel any more Jewish than I feel anything else. I have a non-Jewish wife and effectively, my kids aren't Jewish. The tribal stuff has been mostly unhelpful, [from what] I see in other people." He describes how he always had feelings of inadequacy. "I felt the same way when I went to university. People remember me as being confident, possibly obnoxious, whereas I was actually terrified. I was surrounded by all these public-school boys and girls who were very confident. They had cars, sex lives and bank accounts. They were looking forward to a life of entitlement - a section of society that I had never imagined to exist." It was while at university in Bristol that Isaacs got involved with the drama group (one of his more memorable parts involved being castrated with a cheese wire). From there, he went to the Central School of Speech and Drama, and soon after leaving got his first break in the ITV series Capital City. Since then he has worked steadily. None of his roles can be described as leading-man types, but they are all the more interesting for it. This year sees the release of Good, the film based on the CP Taylor play, in which Isaacs plays the Jewish friend of a writer whose books attract the attention of the Nazi party. "I was reading the diaries of Victor Klemperer [the Jewish academic who kept a diary from 1933 until the end of the war] and immersing myself in some of the writing from the 1930s in Germany," says Isaacs. "To find how so many people simply couldn't conceive of [the rise of National Socialism] going on any longer; good, decent Guardian-reading types couldn't imagine that this thug could stay in power. Also Jewish people too felt that, although they were being scapegoated in many ways, they could sense that the country was getting better, and that more and more moderate people were joining the party, and surely this antisemitic stuff was going to come to an end soon." He takes his research very seriously. For Brotherhood, his character suffered brain damage after being badly beaten, and Isaacs spent time at a clinic for people with brain injuries so he could better understand his character's difficulties. "There was a couple in Rhode Island ... she had come off her bike, on a bike path wearing a helmet, and she had brain damage which took her a long time to recover from. There were people who had suffered far worse than she had but her story stuck with me. She said, 'I haven't made a joke. I'm desperate to have a dinner party and be able to say something witty.' That's the stuff that stays with me". · Brotherhood, Sundays, 10pm, FX Channel.

|